Saturday, September 30, 2017 -  Becchina,Becchina archive,Christo Michaelides,Christos Tsirogiannis,Dick Ellis,Fiorilli,giacomo medici,illicit trade in antiquities,illicit trafficking,Paolo Ferri,Robin Symes

Becchina,Becchina archive,Christo Michaelides,Christos Tsirogiannis,Dick Ellis,Fiorilli,giacomo medici,illicit trade in antiquities,illicit trafficking,Paolo Ferri,Robin Symes

No comments

No comments

Becchina,Becchina archive,Christo Michaelides,Christos Tsirogiannis,Dick Ellis,Fiorilli,giacomo medici,illicit trade in antiquities,illicit trafficking,Paolo Ferri,Robin Symes

Becchina,Becchina archive,Christo Michaelides,Christos Tsirogiannis,Dick Ellis,Fiorilli,giacomo medici,illicit trade in antiquities,illicit trafficking,Paolo Ferri,Robin Symes

No comments

No comments

Where is the world's largest hoard of looted antiquities? Syria? Iraq? Nope, London.

In deference to new readers of the ARCA blog, who may not be as familiar with the world’s largest accumulation of illicit antiquities, ARCA has obtained the permission of London journalist Howard Swains to republish his Medium article, London’s Loot: The Legacy of Robin Symes, in its entirety.

Swains is a journalist and feature writer with experience across print and digital titles, including The Times, the Guardian, Independent, Newsweek, the Sunday Times Magazine and CNN.

London’s Loot: The Legacy of Robin Symes

How the world’s largest accumulation of illicit antiquities got stuck in the UK, and why nobody can shift them

One morning towards the end of January last year, a white truck bearing the insignia of an Italian removals firm pulled out of the Geneva Freeport in Switzerland and began a 560-mile journey to Rome. By the time it had traversed the Alps and reached the Italian capital, the truck had shaken off its dusting of snow but had attracted a convoy of two motorcycles and two saloon cars, each topped with a flashing blue light.

|

| Image Credit: Carabinieri TPC |

The motorcade pulled up in the Trastevere district, outside the barracks of the specialist art squad of the Carabinieri, the largest such division of a national police force in the world. Officers in stiff military-style uniforms, with black leather gloves and dark peaked caps, helped remove 45 wooden storage crates from the truck, which they gradually began to unpack.

Video Credit: Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale

“Operazione Antiche Dimore” Rome, 22 marzo 2016

A few weeks later, the world’s press mingled around those crates with the Italian Minister of Culture, the Swiss ambassador to Italy and high-ranking national prosecutors. The crates’ contents were now balanced on top or spilled beside, as though in a shabby-chic gallery.

|

| Image Credit - Carabinieri TPC |

To the untrained eye, many of the exhibits may have seemed unremarkable: fragments of vases and frescos; detached statue heads and limbs. But there was no mistaking the quality of the centrepiece — and not only because of the uniformed Carabinieri officers posing proudly for photographs beside it.

|

| Image Credit: ARCA 2016 |

The reclining figures of an elderly man and a young woman, close to life-size and carved from Etruscan terracotta, formed the lids to two sarcophagi, dating from the second century B.C. The rest of the material was of similar age, and was, in fact, of comparable significance: Some of the frescos in the haul were thought to have been ripped from temple walls near Pompeii, or from the UNESCO-listed necropolises of Cerveteri, near Rome.

This was loot — thousands of pieces of it — most likely excavated inexpertly, in the dead of night, from Italian soil some time in the 1970s or 80s. It had then been on an uncertain, smuggled journey out of Italy and into Switzerland, via a skilled but illicit restorer’s workshop. The motorcade that swept it back to Rome was part of its ceremonial repatriation, at least 16 years since its clandestine incarceration in Geneva.

|

| Image Credit: ARCA 2016 |

The Association for Research into Crimes Against Art (ARCA) described the items as “an Ali Baba’s cave-worthy hoard of Roman and Etruscan treasures”. The press persuaded reluctant officials to attach a monetary figure to the artefacts: They were priceless, of course, but had a market value of perhaps €9 million to those who might want to profit from such things.

My interpreter pointed to one of the sarcophagus lids and said, “You see this only under glass in a museum.” Had best-laid plans not been interrupted, that is exactly where it might have one day appeared: the endpoint of a sophisticated trafficking network that, throughout the latter part of the 20th century, transformed invaluable examples of cultural heritage into gallery pieces for the world’s most prestigious museums and private collections.

|

| Image Credit: ARCA 2016 |

The individual most responsible for the gathering in Rome was also the man most notable by his absence. A British former antiquities dealer named Robin Symes was the sole suspect for having once rented the storeroom in the Geneva Freeport from which the loot had now been liberated. Symes’s handwriting was on the outside of the packaging crates; the pages of the British newspapers and the Antiques Trade Gazette that wrapped some objects were almost certainly previously read by him. His fingerprints were all over this stuff.

Once among the world’s richest and most celebrated antiquities dealers, Symes has spent the past decade as a disgraced bankrupt, exposed as a former linchpin in the networks that once traded almost with impunity in such material. But for all Symes’s proven crooked dealings, the full extent of his hidden plunder has still not yet been revealed. Furthermore, although Symes, who is now in his mid-70s, spent seven months in prison for contempt of court in 2005, he has never stood trial for illicit antiquities trading, nor been forced to reveal where he might have squirreled further contraband.

Another cache of Symes’s former stock — possibly the largest known accumulation of illicit antiquities in the world — has been stuck in a legal impasse in London for 14 years. The legacy of his known dealings is now the focus of a complicated liquidation, blighted by squabbles between at least three governments and allegations of procedural impropriety.

The ministries of culture in both Italy and Greece say that material stuck in the U.K. belongs to them, and have lodged appeals for its return. Their stance is supported by prominent archaeologists, whose academic endeavours have long been undermined by tomb-raiders and illicit excavators, turning a profit from desecrating cultural sites. Yet those with a stake in Symes’s former business, as well as a number of creditors, appear to support the sale of the former trader’s stock, insistent that there is insufficient proof of ownership to warrant giving it up.

At a time when the looting and destruction of cultural heritage has never been more prominent, archaeologists await further details not only of the items Symes may have spirited away, but the methods by which he was able to profit for so long from the sale of illegally excavated material. Everyone was talking about the same absent character in Rome, as they sometimes also do in London, Cambridge and Athens. In short, what is still to be uncovered from Symes’s former scheming? And, for that matter, where is he?

---

Robin Symes’s established early biography runs as follows: He was born in Oxfordshire, England, in 1939, and suffered early tragedy when his mother was murdered when he was a toddler. There are few other details about his childhood and schooling, but Symes married at 21 and had two sons, born in 1961 and 63.

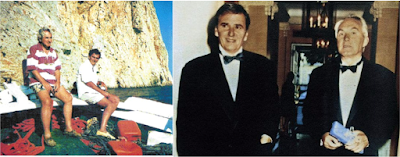

At that time, he was working as a lowly antiquities trader with a shop on London’s Kings Road. But his life deviated sharply from what had seemed to be its likely path when Symes met the handsome Christo Michaelides, a Greek heir to a family of shipping magnates, some time in the 1960s. Michaelides was in his early 20s, five years Symes’s junior, but the pair immediately formed a close relationship that endured for the next 30 years.

|

| Symmes and Michaelides were a couple in life and in business Image Credit - D. Plichon and Iefimerida |

Symes divorced and Michaelides separated from his girlfriend. Although they never openly declared that they were a romantic couple, almost all acquaintances consider the men to have been partners in both life and business, reportedly referred to as “the Symeses”. Their business dealings were apparently bolstered by the almost unlimited finances available to them from Michaelides’s family, and they became the most revered dealers about town.

By the time Symes first came to the attention of the national press in 1979, the level of his business was such that The New York Times reported on his purchase of a Roman glass bowl at Sotheby’s in London for $1.04 million. A decade later, Symes appeared in the Times’s real estate pages, in the process of selling the so-called “Rockefeller Guest House” on East 52nd Street in Manhattan which he had owned for 11 years. “I was here 20 days a year,” he laments as the reason for the sale of the property, designed in 1949 by Philip Johnson for Blanchette Rockefeller. He manages, however, to slip in an anecdote about Greta Garbo once ringing the bell, looking for Johnson. The house sold for $3.2 million.

“Symes acquired a lifestyle to match his success in the antiquities business,” wrote Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini in their 2007 book The Medici Conspiracy. “With Christo he had homes in London, New York, Athens, and Schinnoussa [sic], a small island across the water from Naxos…Symes, who doesn’t drive, was always chauffeured in a silver Rolls Royce or a maroon Bentley.”

Symes and Michaelides lived the high life. They had a gallery in the St James’s district of London; their house in Chelsea had a sunken swimming pool, ringed by exceptional statues; the Schinoussa residence was a sprawling estate across a peninsula, surrounded by the deep blue of the Mediterranean sea.

Furthermore, Symes was a trustee of the British Museum and regularly hob-nobbed with the world’s leading curators. He seemed to have access to the finest antiquities of Greek, Italian, Egyptian and Asian origin, buying and selling through Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Bonhams; placing items in national museums across the world.

“This was before the trustees of the British Museum had rather rumbled the fact that they were buying a lot of material that had recently been looted,” says Lord Colin Renfrew, who is among Britain’s leading archaeologists and is himself a former British Museum trustee. The Museum adopted a new code of acquisitions under the directorship of Robert Anderson, between 1992 and 2002. “That was when Robin Symes was no longer so welcome at cocktail parties at the British Museum, but he had been up to that time,” Renfrew says.

Throughout the 1990s, several investigations moved into top gear in Italy, Greece and the United States into an apparent trafficking network of antiquities. The Metropolitan Museum in New York and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles were only two of the high-profile institutions implicated in having received looted material that had passed through the hands of an Italian dealer named Giacomo Medici.

As detailed in great depth in Watson and Todeschini’s 2007 book, the eponymous Medici controlled a team of “tombaroli”, or tomb raiders, which fed material via a number of well-connected fences, including Symes, to auction rooms and galleries. Symes not only shared a business address with Medici in Geneva, but many of the pieces at the centre of the investigations clearly gained some of their “legitimacy” from once being in the British dealer’s possession. This became especially true after Symes had placed them in museum collections or major auctions, “washing” the items of their illicit past.

In 1988, Symes sold a statue believed to be a 5th century B.C. depiction of Aphrodite to the Getty museum for $18 million. He said it had been in the collection of a Swiss supermarket magnate since the 1930s, and had paperwork to that effect. But the documentation was forged; the statue had actually been looted in Morgantina, Italy, then trafficked via Geneva to London. Experts eventually decided the figure was most likely not Aphrodite, but the misidentification of the character it depicted was far less serious than the exposure of its fraudulent provenance. By the time the statue was sent back from Los Angeles to Italy in 2007, the museum world was in turmoil and mired in similar scandals.

In the opinions of many archaeologists and prosecutors who have studied their activities, the global Symes operation was more significant than that of Medici, whose business was confined to Italy.

“Symes was the biggest illicit antiquities dealer, with Christo Michaelides, in modern times,” says Christos Tsirogiannis, a Greek forensic archaeologist based in Cambridge, who has spent the past decade attempting to unravel the extent of Symes’s dealings and his place in what amounts to a vast global chain. “One can only imagine in the 25-plus year career of Symes and Michaelides how many objects they held and sold if their remains are 17,000 objects of the highest quality from nearly all, if not all, ancient civilisations.”

That remainder — which some people suggest may be as many as 17,000 objects — is what became confined to a number of warehouses in the London area in late 2003. They are the documented leftovers after Symes’s empire collapsed dramatically towards the end of the 20th century.

At a dinner party in Italy in July 1999, Michaelides slipped down some steps, hit his head on a radiator and died from his injuries the following day. As Michaelides’s relatives — the Papadimitriou family — grieved, they also fell into bitter dispute with Symes over the deceased’s estate. (In some form, this dispute remains ongoing.) Symes claimed that the principal business, named Robin Symes Limited (RSL), was his alone and that Michaelides was a mere employee. The Papadimitrious insisted they were entitled to half of its assets as Michaelides was an equal partner. The furious family brought a civil case against Symes in London’s High Court at which he would pay dearly for his hubris in his professional and legal dealings.

Michaelides, left, and Symes hugely under-reported the extent of his “legitimate” business matters in a bid to avoid a costly settlement with Michaelides’s estate. But the Papadimitrious’ legal team hired private detectives to track him across the world. Symes said he had five warehouses of stock; the detectives uncovered around 30. He then incensed the judge, Justice Peter Smith, with a number of lies and diversionary tactics, in particular misreporting the nature of two major sales at a time when he was obliged to share full details of his deals with the court.

Symes said he sold a statue to a company in Wyoming for $1.6 million. The company proved not to exist, and he actually sold it to the Qatari collector Sheikh al-Thani for $4.5 million. He sold a second statue to the Sheikh for $8 million, lodging the money in Liechtenstein, when he reported to the court he sold it for $3 million. (He latterly also sold a furniture collection for $14 million, $10 million more than he reported. He put the money in a bank in Gibraltar.) It turned a civil trial into a criminal conviction.

After throwing out a late claim that Symes was mentally unfit to stand trial, skewering the testimony of Symes’s personal doctor on the stand, Justice Smith sentenced Symes to two years imprisonment for contempt of court. He went to Pentonville Prison in north London, from where he was released after seven months.

By then, having been unable to pay legal costs of up to £5 million, he declared himself bankrupt and receivers seized the official stock of RSL that could be located and then handed it to liquidators. Symes’s own figures, which are possibly inflated, puts the stock’s value at £125 million.

It is this stock that continues to cause controversy and keeps Symes under discussion in the U.K., Italy and Greece. The Papadimitriou family lodged claims of $50 million on the dissolved company, representing Michaelides’s share. Britain’s Inland Revenue was the largest listed creditor, claiming £40.3 million (nearly $70 million in December 2003) in unpaid tax.

Given the nature of Symes’s dealings, the stock almost certainly contains items of highly dubious provenance, and the cultural ministries of at least Italy and Greece have submitted requests for illegally trafficked items to be returned to them. Yet the stock is also the principal asset through which the liquidators could get anywhere near raising the required capital to satisfy creditors. Arguments over it have come to reflect many of the common disputes in dealing with antiquities: there are apparently unresolvable issues over transparency, provenance and proof of ownership. There are also complaints of a lack of cooperation between jurisdictions, and issues with differing laws between countries.

In contrast with stolen material, which might be documented and will be missed if it vanishes, illegally excavated items, by their very nature, are unknown to anybody before the point that they are dug up. Unscrupulous antiquities traders and collectors have long insisted disputed pieces were merely located in dusty attics or storerooms, where they had lain untouched for centuries. Until the UK passed the Dealing in Cultural Objects (Offences) Act in 2003, which introduced the notion of a “tainted cultural item” and shifted the burden of proof to the dealer, it would have been all but impossible to gain a conviction in criminal court for trading in looted property.

Symes accumulated his stock prior to 2003, but the liquidators, a British firm named BDO, are now operating under the closer scrutiny of the modern era, and also since the exposés that clearly linked Symes to looted property. Nonetheless, in 2013, 10 years after the liquidation began, rumours began circulating within the industry that items from the RSL stock were being sold in the Middle East, now the home of some of the wealthiest private collectors of antiquities. Since HMRC, the British government’s tax and revenue service, was the largest creditor with claims on the company, an easy narrative emerged: Was the British government selling looted cultural property to pay back taxes?

Paolo Ferri, a former district judge in Italy, who led the successful prosecution of Medici, told me that he considered any sales of material from the company’s frozen stock was “very scandalous”. He says, “They are selling those items for tax purposes. It’s equal to selling drugs to recover taxes.”

Although now retired, Ferri keeps a keen eye on developments related to Medici’s former associates, and recalls several run-ins with both Symes and the British authorities. Ferri brought Symes as a witness in the Medici trial, but was unable to persuade British police to collect sufficient evidence to put him in the dock. (Before the passing of the 2003 law, British police had no reason to pursue Symes.)

Every six months since December 2004, the liquidators of RSL have filed a report with Companies House, which is the British government’s registrar of corporate documentation. The reports are a matter of public record but only became freely available in June 2015, when Companies House re-launched its website. Although not especially detailed, the documents nonetheless offer the only overview of business matters pertaining to the frozen RSL stock, split between operations in both the United Kingdom and USA.

In the early months and years following the liquidators’ appointment, “realisations” (i.e., incoming payments) include the sale of property, furniture and motor vehicles, as well as a number of sales of unspecified antiquities to buyers in London, Switzerland and the USA. “Disbursements” (i.e., outgoings) include storage and security costs, as well as mounting legal and administrative fees.

The number of realisations have slowed in recent years, but the RSL documents clearly show that there have been numerous sales from the company’s stock. A variation on the name Sheikh al-Thani appears as the purchaser of at least five consignments, costing £326,000, £248,000, £143,300, £127,750 and £57,494 between 2007 and 2010, and there are two entries from January 2014, of £150,000 and £188,000, bearing only the word “Sheikh”. (Al-Thani was the buyer of the material that Symes misreported to the High Court and resulted in his contempt action.)

Other listed buyers include a sizeable list of British and American dealers and collectors, who may be either buying for themselves or as agents for other unknown parties. In June 2015, a consignment costing £52,900 went to a London antiquities trader. The same dealer bought an unspecified consignment in November 2015 for £75,000. They represent the most recent confirmed sales.

By some measure, the largest single sale is listed from November 2008, where two entries apparently refer to the sale of an item described only as “Head of K”. (Other sales rarely have even this much detail.) It appears to have fetched £875,000 ($1.25 million), which remains a significant amount for an antiquity.

None of the dealers I contacted would talk on the record about their purchases from the RSL stock. BDO has also never commented on the liquidation of RSL and turned down my request for an interview. There is no clear evidence that any of the transactions are improper: The argument runs that Symes did not deal only in illicit objects and the company’s stock would also include plenty of material that was not subject to proprietary claims. However, only a relatively small number of the sales have taken place in a public auction, where it might reasonably be expected they would fetch the highest price. This lack of transparency continues to infuriate those who condemn the opaque nature of the antiquities trade, while archaeologists contend that ethical dealers would reject on principle any stock that had once been handled by Symes. They say that the refusal to publicise the details of the items makes it impossible to determine their true provenance, nor where they will end up.

Few people have a better idea than Tsirogiannis about the true nature of Symes’s dealings. In 2006, while working for the Greek Cultural Ministry, he accompanied Greek police in a raid on the property in Schinoussa that uncovered, among other valuable objects, a photographic archive of around 1,300 items that had once been in Symes’s hands. Similar photographic archives were found in the Geneva offices of Medici and a fellow dealer named Gianfranco Becchina, often showing antiquities fresh from the ground, still with soil encrustations on them.

These photographic archives are as close to a smoking gun as investigators get in this field, and access to them is closely restricted. Forensic archaeologists working in Italy used the Medici and Becchina archive to secure convictions against the two former dealers, proving they had sold illicit material. Meanwhile Tsirogiannis, who is one of few people outside a police department or government ministry with full access to the archives, still scours the catalogues of antiquities auctions and museum shelves and regularly identifies items that are depicted, pre-restoration, as recently being in the hands of the convicted dealers.

|

| Image Credit: Howard Swains |

I took a number of photographs of the seized Symes stock displayed at the press conference in Rome and forwarded them to Tsirogiannis. The Carabinieri also released an official video showing their officers handling various objects found in Geneva. We met in Cambridge soon after, when Tsirogiannis showed me 12 positive matches he had made between items in the photographs from Rome and those previously in the possession of Medici or in the seized Schinoussa archive. The items in my pictures, as discovered in the storage crates hidden by Symes, were clean and restored; ready for sale in a high-end gallery. The same items in the Polaroids from the Medici and Schinoussa archives were cracked, dirty and often incomplete, broken apart to facilitate easy transportation. The identifications proved beyond any doubt that Symes dealt habitually in loot. This much had been agreed by the Italian and Swiss authorities as a precursor to the repatriations.

Tsirogiannis has repeatedly offered his services to the liquidators, both directly and via the Metropolitan Police, to examine the RSL stock in London and determine what among it is obviously illicit. The offers have consistently been ignored, leading Tsirogiannis to the assumption that the liquidators would rather sell the items than return them. (The liquidators did not respond to these accusations.)

Allegations of impropriety are sternly rejected by James Ede, a British antiquities dealer and former chairman of the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art, who has been working with BDO as a valuer and industry expert. Ede is a frequent commentator on the antiquities trade, often providing the lone voice in defence of an industry that he says has cleaned up a great deal since Symes’s heyday.

Ede denies that the liquidation is being conducted behind a shroud of secrecy. He told me in an email that “the liquidation is being carried out entirely properly with due reference to all interested parties”. He agreed during a subsequent telephone conversation that his italics suggested a concern for the creditors on the RSL account who have still not seen even a small fraction of the money they have claimed.

Ede also says, however, that he is not permitted to answer questions about the contents of the warehouses, the complexities of the issues facing the liquidators, nor to address the particularly controversial subject of sales. “There is a perfectly reasonable desire sometimes to have confidentiality in ones business dealings, and there’s nothing wrong with that,” he says.

The name of Ede’s company, Charles Ede Ltd., which was established by James Ede’s father, features prominently on the liquidators’ documents at Companies House, most notably alongside the “Head of K” sale. However, Ede told me that neither he nor his company has made any purchases from the stock, leaving it unclear why the company name would appear in the “Realisations” column. The implication appears to be that the object has gone to a third party, who would rather not appear on official documentation.

One dealer with close knowledge of sales from the stock, but who did not want to talk on the record, told me that sales are accompanied with long and detailed paperwork indemnifying BDO against subsequent proprietary claims. Wherever the items are ending up — and nobody was prepared to speculate — the liquidators appear to be making sure that they do not latterly face legal reprisals, should allegations emerge that cast doubt on the material’s provenance.

The liquidation clearly still has some way to go. Over 17 years, the documents show total disbursements from the RSL account of approximately £13.35 million and realisations of £13.72 million, a net gain of slightly less than £400,000. In the 12 years since the liquidators have been submitting invoices, fees for their services run to more than £3 million.

The documents also suggest that significant material still appears to be in the liquidators’ possession. The most recent filings, covering the 12 months up to June 2017, reveal £34,356 was spent on insurance and £63,421 (plus VAT) went on storage. Fees from previous years are higher, but the general trend points to an attempt to consolidate the hoard in fewer locations. (US dollar exchange rates, which will have fluctuated, were calculated in September of this year.)

The contents of the warehouses remain a mystery to all but a select few. In Rome, I visited an Italian prosecutor named Maurizio Fiorilli, who now represents the Italian state in its negotiations with BDO over the RSL stock. Italy claims that there are items in the warehouses that were looted from its soil and therefore should be returned to the country. Fiorilli, like his friend and former colleague Paolo Ferri, is a veteran of battles to protect Italian cultural heritage and keeps on his bookshelf a photograph of the two men posing beside the so-called “Euphronios krater,” one of the most exquisite — and notorious — antiquities in existence.

The krater, which is a terracotta vase-cum-bowl used for mixing wine and water in the ancient world, is the only known complete example decorated by the master painter and potter known as Euphronios, who was active in Athens between 520–480 B.C. In 1972, the Metropolitan Museum in New York bought the krater from an American dealer named Robert Hecht for $1 million, which was then a record for an antiquity. However, Hecht had fudged the provenance documentation, disguising that he had obtained it from Giacomo Medici. After a lengthy legal tussle, in which Fiorilli was prominent, the museum gave up the krater in 2006.

Fiorilli’s discussions with BDO over the Symes hoard focus specifically on a list of around 1,000 objects submitted by the liquidators to the Italian Cultural Ministry as being potentially of interest. Fiorilli says he knows of no sales from this specific list of disputed items, but details a frustrating series of obstacles and delays that have drawn out negotiations and precluded any repatriations.

In October 2007, Fiorilli was granted access to some of the warehouses holding the RSL stock, which he toured in the company of lawyers of the liquidators, an appointed gallery expert and an officer from the Metropolitan Police. Fiorilli says that what had been scheduled to be a three-day visit was cut short, without explanation, at the end of the first day. He says he was also asked to sign a non-disclosure agreement that prohibits him from answering specific questions about what he saw.

Nonetheless, Fiorilli invited me to look at the computer screen in his office as he opened a folder of 421 photographs labelled “Symes Depository”. He flicked apparently at random through images of statue fragments, small figurines, vases and reliefs; a collection not dissimilar to the items displayed at the Carabinieri’s press conference. One scrap of paper bore the name “Von Bothmer”, almost certainly Dietrich Von Bothmer, who was formerly a curator at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, with a specialisation in Etruscan vases. Fiorilli also said he saw closed boxes in the warehouses that seemed to have come from the Met, but was not permitted to open them. Another fragment of paper bore the single, hand-written word, “Euphronios”. Fiorilli shrugged when I asked what it might refer to.

“The negotiations were interrupted several times because of more and more questions by liquidators and ever new demands for a revision of what has been agreed,” Fiorilli says. “The negotiations have lasted for nine years and the liquidators have had evidence for over seven years that the objects included in the lists provided by them belong to the Italian cultural heritage.” (This conversation took place in April 2016.)

Lord Renfrew openly pondered whether any sales from the RSL stock could be regarded as in violation of the 2003 law that prohibits dealing in “tainted” material. Renfrew, who sits in the House of Lords in the British parliament, is keen for the country’s lawmakers to step in and halt the sales on behalf of the Inland Revenue. “The British government needs to be prodded to come into the open on all this shady dealing,” Lord Renfrew told me. “It’s not clear they’re breaking the law but they really are behaving unethically, even by the government’s own ethical standards.”

I attempted to speak with representatives of the Department for Culture Media & Sport in both the present and former governments, but no one admitted any knowledge of the Symes warehouses nor discussions to repatriate items.

According to a professional liquidator I interviewed, who spoke on the condition of anonymity as she is not permitted to comment on specific cases, it is not quite accurate to say that any sales from the stock will go directly to pay taxes. Although HMRC is owed more than £40 million from the dissolved company, it is only one of a number of creditors and will receive no preferential treatment. However, the liquidator questioned the lack of public auctions, and expressed her surprise that the impasse could last this long with no obvious benefactor.

The London-based lawyers representing the estate of Christo Michaelides told me that they consider matters to be largely out of their hands. They have a number of cost orders outstanding but do not expect significant, if any, financial remuneration, even though the Papadimitriou family are known to have spent many millions in pursuing Symes. The family also remains the second-largest creditors with claims on the RSL stock and, in 2005, the family’s Greek lawyer told a documentary that if expenses began to escalate “it will be obliged to liquidate the objects in auctions.”

The London lawyers said these matters were entirely in the hands of the liquidators. Although they keep a “watchful eye” on activities related to Symes and RSL, they have little contact with BDO beyond receiving a letter once every six months.

More pertinently, perhaps, Fiorilli says that the delays in permitting the tainted material to return to Italy has allowed the statute of limitations to pass on any crimes allegedly perpetrated by Symes. Both Ferri and Fiorilli have previously been keen to prosecute Symes in Italy for crimes related to looting, smuggling and theft but the law requires key evidence to be in the country in order to secure a conviction. Referring to crucial documentation, photographs and items currently in the possession of BDO, Fiorilli told me, “If we had this, in the time limit, Symes would go to jail.” He added, “The interest of the Italian Government was and is exclusively cultural. The interest of the liquidators is purely commercial.”

I received conflicting reports during the reporting of this story as to whether Symes remains a wanted man. Tsirogiannis showed me an email sent by Fiorilli in September 2013 in which the Italian prosecutor said he had heard that the Greek government had issued a warrant for Symes’s arrest. The Greek ministry of culture told me that they have assembled a committee to oversee all matters pertaining to Symes, including its claims on the RSL stock. But the ministry had still not replied to my written questions more than 18 months after I first submitted them, despite a long email correspondence with its press department. Fiorilli did not offer further comment on this specific point.

London’s Metropolitan Police told me that it has “no current investigations in this matter”, even though Tsirogiannis showed me another email in which the head of the force’s recently-disbanded Art and Antiques Unit asked him whether he knew of any tainted antiquities anywhere in London. In his reply, Tsirogiannis mentioned the RSL warehouses, which he is certain contain numerous illicit items. The email chain ended there.

Renfrew is now the co-chair of an All-Party Parliamentary Group for the Protection of Cultural Heritage, which has been established in the British parliament in response to reports of recently looted material from Iraq and Syria arriving on the domestic antiquities market. Both Renfrew and Tsirogiannis have made specific mention to Symes in the group’s meetings, which have entered the official minutes. They note that the absence of claims on the RSL stock from Iraq and Syria does not mean looted property from those countries is not already in the UK, but it would pre-date the Bashar al-Assad and ISIS era.

The archaeologists remain angry that the disputes over the RSL stock have denied authorities the opportunity of fully exploring the world in which Symes operated, leaving the market murky enough, in their opinion, that illicit material can still find a way through the networks.

“Because of the lack of cooperation, communication among various stakeholders, authorities, governments, museums and so on, we will never know any of these different sectors regarding Symes’s activities,” Tsirogiannis says. “This is our only chance…to understand and highlight a small part of this huge area that is called ‘antiquities market’…Either we use this evidence and we use it quickly, now, or we are losing the best opportunity we ever had.”

Understanding the illicit trade is seen by archaeologists as more important even than the repatriation of items. As with all improperly excavated objects, the damage is already done the moment they are taken out of the place they had lain for thousands of years. The value to research lies in understanding how the items were used in antiquity; clandestine excavation immediately eliminates all possibility for contextual analysis. To archaeologists any residual “beauty” of an item is an irrelevance.

The unrest in the Middle East of recent decades — in particular the plundering of Syria and Iraq by all of ISIS, other rebel groups and troops loyal to Bashar al-Assad — will almost certainly fuel a fresh interest in antiquities, and flood a new market. Archaeologists contend that many of the smuggling networks established in Symes’s era remain intact, and say that politicians’ recent rhetoric condemning cultural destruction is empty given their unwillingness to deal adequately with items previously stolen from overseas territories.

Symes himself is no longer considered a prime target. I encountered limited enthusiasm from archaeologists and authorities alike to see the former dealer return to the dock. The general consensus is that other warehouses are likely still scattered across Europe and the USA, but that even he will have no idea where. Most people I spoke with seemed to suggest belated prosecution, even if it were possible, would serve little purpose.

One dealer told me he heard that Symes now lived “above a fish and chip shop”. Another said he’d heard rumours that Symes was “close to death”. The lawyers representing the Michaelides estate said they last served papers on Symes in 2010 when he was living behind a church in east London, occupying himself with copper etchings. They said he had now moved.

Peter Watson spoke to Symes while reporting The Medici Conspiracy in 2006, and Symes also agreed to meet a Greek documentary film crew at his lawyers’ office in the same year, but pulled out of the interview at the last moment. The documentary crew filmed the last known pictures of him arriving to the lawyer’s London office — a healthy-seeming, smart man in a dark suit jacket, with short, grey hair, clutching a bag under one arm, with an overcoat draped over the other — before vanishing inside.

Screenshot from Greek documentary “The New Files”

A former Scotland Yard detective named Dick Ellis, who had previously interviewed Symes in the 1990s, says he believed the former dealer was now living “among friends”. Ellis says that he would be able to locate Symes quite easily if anybody had a will, and the finances, to do so. (Symes’s former wife died in 1995 and one of his sons two years later. His surviving son, Innes, runs a construction company in Bristol, but told a Daily Mail reporter in February 2016 that he had not seen his father for 10 years.)

A tour of Symes’s London is a lonely exercise these days. His former gallery in the affluent St James’s district in the centre of the city is now a private office, from which the marble-effect plate bearing the former tenant’s name has long been removed. His preferred warehouse in Battersea, close to the former smugglers’ passages that flanked the River Thames in its mercantile pomp, is a characterless structure on a modern trading estate behind fierce anti-climb railings. Symes once brought the curator of the J. Paul Getty Museum there to show her the disputed Aphrodite statue ahead of its $18 million sale.

Meanwhile the residence in Chelsea, which Symes shared with Michaelides, still oozes wealth from behind its shuttered windows and wrought-iron fence. But it is an impenetrable compound, where Symes would be most unwelcome: The name on the most recent electoral register for the adjacent property is Nicolas Papadimitriou, Michaelides’s brother-in-law, who financed the civil litigation that sent Symes to prison.

Symes gave a remarkable interview to the Los Angeles Times from his cell in Pentonville in 2005, in which he continued to portray himself as some kind of rock-star. Symes described himself as a “legend” and remembers the moment an unknown “fan” planted a kiss on his mouth in a nightclub, for no reason beyond the fact that “You are Robin Symes…You’re to the world of art dealers what the Beatles are to music.”

Wherever he is now, Symes’s rock-star days are over. But the squabbles over his unfortunate legacy remain fresh, and maybe more relevant to contemporary culture than ever before.